Features

Exploring Atlantic salmon genetics

Where are we and where can we improve?

November 1, 2021 By Catarina Muia

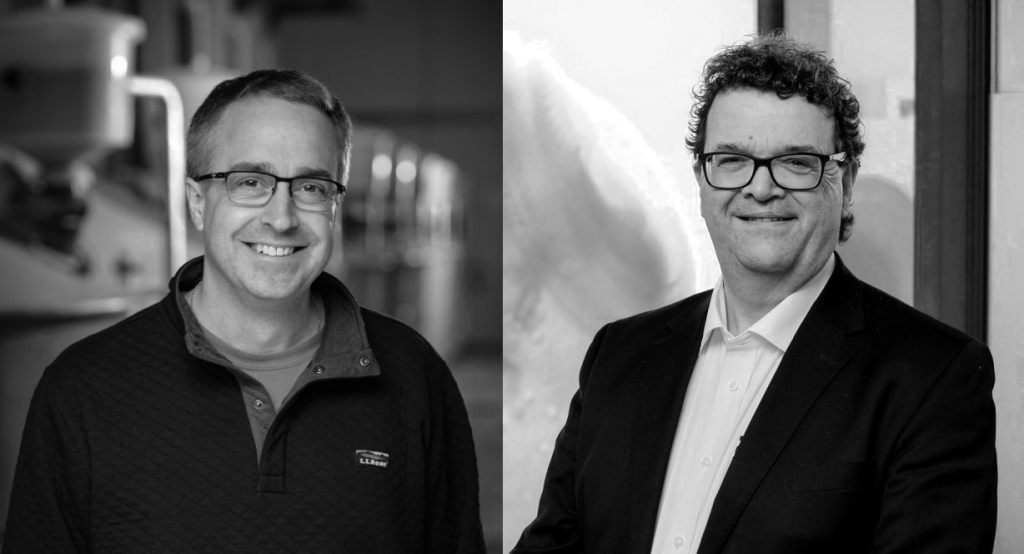

(Left) Christopher Good, Director of Research at the Conservation Fund Freshwater Institute. (Right) Dr. Jónas Jónasson, Production Director at BMK Genetics & CEO at Benchmark Genetics Iceland.

(Left) Christopher Good, Director of Research at the Conservation Fund Freshwater Institute. (Right) Dr. Jónas Jónasson, Production Director at BMK Genetics & CEO at Benchmark Genetics Iceland. The recirculating aquaculture system (RAS)-produced Atlantic salmon sector has come a long way since its inception in the late 1990s. According to RAStech’s sister magazine, Hatchery International, the first handful of RAS were effectively used to produce millions of Atlantic salmon smolt in North America and most other major salmon producing countries around the globe. Since then, the industry continues to strive for success, with a handful of companies reporting successful harvests since 2018.

It took time to get the technology there though, with RAS components such as micro-screen drum filters, oxygenation systems, tanks and biofilters evolving greatly in the past 23 years. Today, the industry continues to look at how to improve technology and RAS facilities to produce high-quality Atlantic salmon. In order to be successful, the industry must pay close attention to the biology of Atlantic salmon as well, focusing on genetic improvements to not only create quality stock but to avoid diseases, mass mortalities, and early maturation. These issues have been experienced less frequently in the past few years, but it must still be addressed in order for the industry to move forward.

Curious to know where the industry is headed in genetic enhancements or modifications for the improvement of RAS-produced Atlantic salmon, in the most recent episode of the RAS Talk podcast, co-host Brian Vinci, director of the Conservation Fund Freshwater Institute and I, sat down with Dr. Jónas Jónasson, production director at BMK Genetics & CEO at Benchmark Genetics Iceland, and Christopher Good, director of research at the Conservation Fund Freshwater Institute.

A biologist from the University of Iceland, Jónasson acquired his PhD in genetics from the Agricultural University of Ås in Norway and in his current role, is responsible for all production sites across Benchmark Genetics for Atlantic salmon.

As the director of research at the Freshwater Institute in Arlington, Va., Good began working at the institute in 2007 and his research has focused on improving the sustainability of the aquaculture industry through enhanced health and welfare of farmed fish, with a recent emphasis on Atlantic salmon grown to market size in closed containment water recirculation facilities. He is involved in peer-reviewed and industry publications, lectures at conferences and workshops, and has frequent interactions with government, industry, and private non-profit stakeholders. Good has been a diplomate of the American College of Veterinary Preventive Medicine since 2017, and a certified aquatic veterinarian with the World Aquatic Veterinary Medical Association since 2014.

RAS Talk: You both have such an impressive list of credentials and years of experience in the aquaculture industry, could you both talk to me about your journey through the years in the aquaculture industry and what your focus is on today?

Jónas Jónasson: I started my career in 1989, gathering eggs from Norwegian stocks in Iceland to create a base population for salmon genetics in Iceland. Since 1991, we have been doing land-based farming here in Iceland using a flow-through system, which was mainly designed to produce eggs all year long. This is because at that time there was a huge demand for eggs to be imported into Chile and as you may know, they’re off-season from us in Iceland. This is why we came up for the idea of producing eggs all year ‘round. It was successful then, and is still very much a success now. At the same time, being on-land, it is a highly biosecure system as we need to avoid contracting any diseases that can occur in cage farming. Since then, I’ve considered myself very privileged, being involved in such enjoyable work and being part of the industry as it has developed. You can imagine while I was studying in Ås for my PhD, we made dianetic plans for the industry to reach around 100,000 tons. You can imagine now, it’s getting closer to 2.5 million tons, so it has been a journey.

Chris Good: My career in aquaculture started in the late ‘90s. I was a technician at a fish health laboratory in Ontario, Canada, working with the Ontario Ministry of Natural Resources, Fish Culture and Hatchery Systems. We were a diagnostic lab that was screening the fish for pathogens and it was around that time that I became interested in aquaculture in general. I realized that there weren’t many people interested in aquaculture at the time, so I chose that path. I did a concurrent doctor of veterinary medicine (DVM) and PhD, with a career in aquaculture in mind. It was great timing because when I defended my PhD, I did it on a Friday and the Freshwater Institute job came up at the same time. I drove down to Shepherdstown and gave the same talk on Monday. Thankfully, they had me onboard and I’ve been there since 2007. I started off as an aquaculture veterinarian, working primarily on the fish health aspect of our research program. I’m now the director of research at the Institute. It’s a great place to work, it’s all open book where we’re trying to help the industry expand in a sustainable manner. It’s a great team all around and I feel so privileged to be in that position.

RAS Talk: For those of you who put two and two together, Chris and I both work together at the Freshwater Institute. It’s a pleasure to have you on the podcast, Chris, to talk about some of the research we’re doing at the Institute and specifically, what you are working on. Before we jump in, I’d like to quickly ask Jónas about Benchmark and StofnFiskur. Many of the folks in the salmon farming industry know StofnFiskur as a premier source of Atlantic salmon eggs. Of course, it appears that the name has gone, but all you folks are still around working under the Benchmark umbrella, correct?

JJ: Yes, we changed the name last January from StofnFiskur to Benchmark Genetics Iceland. The strain itself is still called StofnFiskur, so the name is still there. We are going to improve the StofnFiskur strain moving forward and we’ve create production systems in northern Norway, which is in principle, based on information we have in Iceland. We have a year-long surplus of eggs from Norway now. Simultaneously, we are building up our production system in Chile as well, allowing for a biosecure strain, based on our strain from Iceland, to be produced in any season.

RAS Talk: Jónas, what are some of the current genetic improvements needed for RAS-produced Atlantic salmon, in order to eliminate some of the sector’s more pressing challenges? Additionally, how are you actually making these improvements, year over year?

JJ: The most important trait for all aquaculture is to improve growth rate; this is our main focus. In land-based farming, we have some challenges around maturity, which I will touch on later. But as the industry moves forward, I’m sure we will have other traits to consider, especially if it’s related to health, such as diseases. Moving forward, we have breeding for discolour and fat content, and quality of the flesh. That will be a major focus, but growth rates is the main one.

RAS Talk: How do you acquire the information needed from the growers, then make the improvements from the broodstock you have. What does that process look like?

JJ: We have tested our families with land-based producers before and we are putting on programs in different countries to do that. But we have to remember that since we’ve been land-based in Iceland, we use the information for the growth rate on land in Iceland, for eight generations. During these eight generations, we have doubled the growth rate since we started back in 1991. It’s a continuous process. At the moment, we think we can very easily produce 4 or 5 kilo fish in 20 to 24 months, based on different systems. A continuous selection is going to improve about one week per year, so it’ll just be a continuous process.

RAS Talk: You mentioned maturation earlier. Can you explain how early maturation is taken into consideration when you’re doing your genetic improvements for the Atlantic salmon broodstock?

JJ: In general, maturation isn’t the problem when it comes to maturation in the Northern Hemisphere. We control that in cages with lights and such. When we come on land we have challenges with maturation, especially if we’re in freshwater, this is less of an issue in saltwater. But in freshwater, especially in higher temperatures, perhaps over 11 or 12 degrees. To overcome this, we have considered just increasing selection on the trait, but moving forward we saw a much simpler method, which was to go on and produce all female stocks.

We have, in-house, all females for all the land-based producers in the world, whenever they need. We created a cryobank so we have a frozen milto to produce all females, whenever needed. Interestingly, we did some research also with Freshwater Institute where they’re using triploids, and we can use those. They’ll never mature, but there is some skepticism of using triploids, but we can do it. In short, the first thing is to have all females, then you can do all female triploids, and later on, we’ll look at what options we will have in the future.

RAS Talk: Chris, what research is currently being done by the Freshwater Institute, to eliminate these challenges experienced in RAS-produced Atlantic salmon. How are you and your team working with breeders like Jónas, to overcome these issues?

CG: There are still plenty of challenges remaining in the RAS production of salmon. It was discussed earlier that early maturation is probably one of the biggest ones and for any listeners wondering how this impacts a farmer: mature fish at harvest are generally a downgraded product. The gonad growth often pulls out pigment from the flesh, so you wind up with a pale fillet, for which you won’t receive a premium price, so a farmer really wants to avoid early maturation. Lately we’ve been assessing the impact of rearing temperature on early maturation in salmon post-smolts and therefore, we’re actively researching that area.

Another challenge that’s specific to RAS-produced salmon is off-flavour, which is essentially an earthy, musty smell that can be imparted upon fish that are raised in RAS. Fish need to be purged of off-flavour after production. There’s a period of time when they’re in a purge system where they are off feed, receiving water from a system that has been disinfected and doesn’t have the biofilms that produce off-flavour compounds. So, if a farmer was able to avoid that process entirely, that would be a wonderful thing for the industry. We’re actively researching that area. In terms of working with breeders like Jónas, our current United States Department of Agriculture (USDA) five-year project plan is studying two different strains.

We are currently wrapping up one now that’s looking at steelhead and we’re starting our next trial, looking at Atlantic salmon. We’re looking at a range of strains within each of those species, determining which perform best in a RAS environment. These fish have been bred over the years for performance in more traditional systems, so we want to know which of these strains will actually do better in a RAS grow-out. I think the Atlantic salmon study will be very interesting. We’re going to provide Jónas with additional information about the fish that he has provided us. He’ll be able to assess, more in-depth than we can, the genetic variation and the performance of the individual strains within the StofnFiskur strain. That’s where we’re at right now. I’m really hoping we’ll be able to determine which strains work best in a RAS environment, and provide that information to the industry.

RAS Talk: As improvements continue to be made to the genetics of Atlantic salmon, what are some specific biosecurity measures you feel must be incorporated into a RAS facility, to optimize these strains?

CG: For biosecurity, the biggest one would be selecting strains resistant to specific diseases that you might encounter in RAS; think about opportunistic pathogens. For rainbow trout and Atlantic salmon, the USDA is looking at these things and are trying to breed for disease resistance. I think also, what Jónas was talking about earlier in regard to developing RAS, late maturation and even sterile-type strains will help biosecurity as well. Early maturing fish do have a tendency to be susceptible to opportunistic pathogens, just because it’s a fairly stressful process for them. I think that is part of the parcel with maintaining good biosecurity.

I do think there are two parts to your question, and I think the other is bio-containment. If the facility really needs to consider bio-containment, that would depend on where the site is. For example, a large facility in Florida might not have to worry much about bio-containment because escapees simply wouldn’t survive outside of the facility’s environment. However, a similar facility in a place like Maine, for example, this might be a bit more potentially-problematic. It would require some efforts to ensure that escapees wouldn’t be an issue. You need some type of physical exclusion methods to prevent escapes because otherwise, there is the worry that a potential escapee might cause some genetic interference with wild stocks which in Maine, are already endagered.

Print this page