Features

Aquaponics

Management

Sustainability

Bringing fish farming closer to the dining table

September 21, 2020 By Jennifer Brown

Food supply chain and climate change concerns are giving developers of aquaponic systems greater reason to believe their indoor operations — that bring together the production of fish and growing of vegetables under one roof — can help feed the planet.

Aquaponics has been an emerging area of environmentally sustainable food production since the mid-1990s, as people become more concerned about how their food is produced and how far it has to travel. Proponents of the technology behind the process are seeing greater adoption. In fact, aquaponics is set to see a 12.8 percent compound annual growth rate, according to a 2019 report from Meticulous Research.

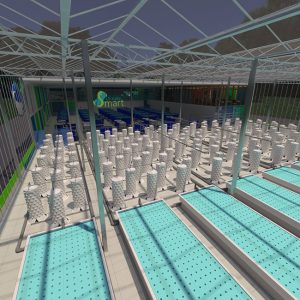

Aquaponics combines recirculating aquaculture systems (RAS) with hydroponics within the same closed water system. This provides an opportunity, says João Cotter, CEO of Aquaponics Iberia, for urban areas to have a local fresh food source, producing vegetable crops and protein source year-round all without the threat of drought or other effects of a changing climate.

Imagine an aquaponics restaurant on the roof of a condominium or as part of a community center. Cotter’s Fish n’ Greens concept incorporates the growing of fish and vegetables in one facility one step further as a destination for those who want to see how their food is grown before enjoying a meal.

Urban flair

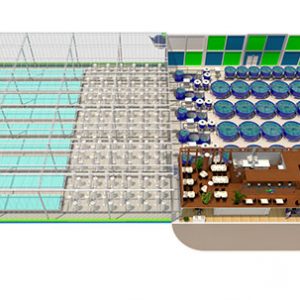

Based in Torres Vedras, Portugal, Aquaponics Iberia has developed Fish n’ Greens to be an aquaponic food production and immersive consumer experience for urban locations. The “smart farming for smart cities” concept will include a food store and restaurant, guided tours of the facilities, and research conducted onsite.

As proposed, the facility will have the capacity to produce up to 45 tons of fresh fish and 130 tons of greens per year, says Cotter.

“It can grow more, but we are being quite conservative, initially. It is safer to run 40 to 50 kilos per cubic meter, and that can grow 45 tons of fish per year and 130 tons of vegetables from one facility.”

“We are integrating land-based and urban aquaculture with healthy produce into a unique ecosystem,” says Cotter.

Some of the fish that will be produced include Basa catfish.

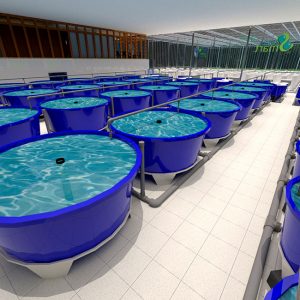

The company has been developing the project since 2013. The facility will feature a RAS with 24, 10-cubic-meter tanks.

“We are still trying to get funding and looking for investors for the first unit,” says Cotter.

According to Meticulous Research based in India, “high initial start-up costs and critical management requirements are the key factors hindering the adoption of aquaponics farming.”

The company has applied for funding from the European Commission and is participating in other programs to finance and get grants for the financing required for the capital equipment investment, which is estimated to be €1.8 million (US$2 million) for the first production cycle.

“We are partnering with the municipalities – they are renting us the land in urban areas. We are proposing to provide programs in common with them, such as school visits and workshops for food education and good food habits with guided tours on sustainability,” says Cotter.

- The proposed RAS facility will include 24, 10-cubic-meter tanks.

- The Fish n’ Greens concept of bringing urban farming closer to consumers by building a restaurant on top of its aquaponics farm, offering consumers a first-hand look at how their food is produced.

Technology is key

Lethbridge College senior research scientist Nick Savidov has been involved in aquaponics for more than a decade and says success with these kinds of projects demands the use of the latest water and waste treatment processes.

“I would say aquaponics is the future,” says Savidov. “But you need to use modern technology in fish production, plant production and most importantly the water and waste treatment.”

To be successful, Savidov says commercial aquaponic operations have to utilize modern water treatment methods similar to the water regeneration used in RAS, but the nutrients must be preserved.

Aquaponics Iberia’s Climate Smart modular technology uses solid filtration, aerobic biodigesting (conversion to fertilizer), and O2 management and control. Cotter says the system allows for higher productivity with lower inputs in terms of water, energy consumption and maintenance requirements.

“It is a bit different than regular aquaponics,” says Cotter. “What we have noticed is that in common aquaponic systems – particularly in Europe – most of the systems have issues with solid waste management. We have applied more of the technology used in RAS, and put in biofiltration and biodigesters to take care of the solid waste coming from the filtration system.”

With the biodigester, Cotter says most solid waste can be converted into liquid fertilizer and put it back into the system according to the nutrient levels.

“We take most of the solids out of the system and use it for other purposes such as irrigation agriculture or organic agriculture – it’s a by-product that is valued,” he says.

Savidov says the use of aerobic biodigesters is not common but he has advocated its use in aquaponic projects for years.

“I’m very glad this concept has started spreading around the world. I started using aerobic bioreactors 16 years ago and went around the world to convince people. Now we see people using biodigesters, and I’m especially glad they’re doing it in Europe,” he says.

About 50 percent of the waste coming from the system ends up being solid waste used as compost for organic agriculture and isn’t returned to the aquaponic system.

Aquaponics uses up to 95 percent less water than traditional farming with no pesticides or synthetic fertilizers. Fish waste is converted into a natural fertilizer that feeds the plants. By consuming the nutrients, the plants leave the water cleaner and ideal for the fish to thrive.

Growth spurt

It is estimated the global aquaponics market could be worth $1.4 billion by 2025, growing at a compound annual growth rate of 12.8 percent, according to a report issued in July 2019 from Meticulous Research. The report cited changing climate change conditions around the world as the primary driver behind the growth of the market for fish and vegetables being grown in a soilless environment.

The market is segmented by equipment (grow lights, pumps and valves, fish purge systems, in-line water heaters, aeration system, and other equipment), product type (fish, vegetables, herbs, and fruits), application (commercial, home production and other applications), and geography.

North America had the largest share of the global aquaponics market in 2018, followed by Europe and Asia Pacific. China, India and Australia are expected to see the highest rate of adoption over the next five years.

Savidov notes that large commercial aquaponics facilities, such as Superior Fresh in Wisconsin, have been quite successful. They are producing four million pounds of organic greens, salmon and Steelhead each year.

- Aquaponics Iberia plans to produce up to 45 tons of fresh fish and 130 tons of vegetables from one aquaponics facility.

- Digital rendering of Aquaponics Iberia’s planned aquaponics production facility

Urban food production

“By using our technology and taking care of solid waste in a more efficient way with the biodigester, we can get an additional 20 percent savings on top of what is common with aquaponics. We can get 95 percent water savings compared to conventional farming methods,” says Cotter.

Cotter hopes the concept of Fish n’ Greens is embraced as a sustainable food option in Europe where it is less understood than in the United States.

“The difference between Europe and the U.S. is the fact that here, aquaponics cannot be certified as organic as it has to be grown in soil for that designation. When we sell to the supermarket, we can’t have that differentiation, so the best way we do it is to locate the system in the city and let the customer visit and create awareness of aquaponics and try to let them understand the difference,” he says.

Cotter hopes that when consumers see the symbiotic ecosystem at play, they will understand what is different about aquaponics, and they will give it a try.

Despite the high start-up costs, Cotter says he believes it will eventually be an in-demand product at a reasonable price.

“For the first one to three years, the price will be aligned to saltwater aquaculture fish like Atlantic sea bass and Mediterranean sea bream – about €6 to €7 per kilo,” he says.

Print this page